In a discussion with Malaria No More, Professor Wendy O’Meara of Duke University, a lead malaria researcher, shares the results of Kenya’s first-ever Seasonal Malaria Chemoprevention (SMC) pilot project conducted in Turkana Central and how it demonstrated that it could reduce malaria cases in children by more than 70 percent.

Can you tell us about the pilot program?

O’MEARA: I’ve been working in Kenya the past 15 years. But several years ago, a colleague of mine working in the Turkana region suggested we come take a look at malaria there. At the time, the prevailing view was that malaria wasn’t an issue there, because in the far northwest corner of Kenya, the region is extremely arid and gets less than 25 centimeters of rain each year. So, we were thinking, maybe malaria was occurring there because it was being imported from other regions and causing brief outbreaks? To test this, we started doing surveillance at airports and bus stations to see what parasites were being imported. What we found was that parasites were being imported and even winding up being transmitted to residents, but at a smaller scale than suspected. Instead, we realized malaria was endemic and with lots of local transmission and that about 1 in 3 people, or a third of the population, had malaria asymptomatically in the community. That’s a huge burden of malaria.

We started talking to the National Malaria Control Program and working with the communities there. One issue we discovered was that many of the families in Turkana are nomadic pastoralists, meaning they move with their animals. So, we started having the herders wear trackers for several months when they’d go out with their animals, and we could see where they aggregated around water with herders from other places. And we found that they were, in fact, bringing back parasites to their home villages from other communities.

But in these communities, just giving children nets wasn’t going to be very practical since many of them sleep on the ground outside, where it is difficult to install a net. Families don’t carry nets while they are moving around. So, we started thinking about what other measures were available to protect these kids during the transmission season.

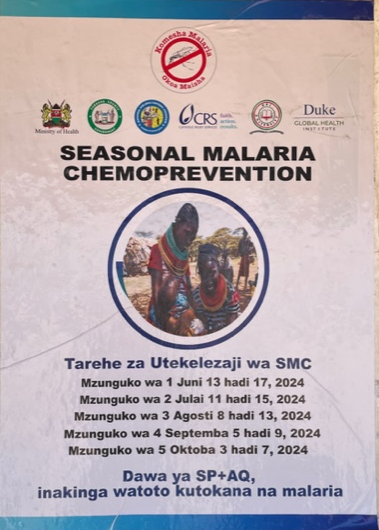

Around that time, the World Health Organization had changed their recommendations around seasonal malaria chemoprevention (SMC), so we started thinking it could be an ideal solution given malaria in Turkana is highly seasonal. As you know, SMC involves giving a course of drugs to every kid once a month, but it must be well timed, which isn’t easy when the families are moving with their animals regularly.

But we did some baseline work with the county health team to tailor and design the delivery strategy to meet the needs of the community. And we rolled out SMC for pastoralist communities in five monthly cycles in 2024. We also had some funding from the President’s Malaria Initiative to help us do the evaluation, and we were able to show that we prevented 70% of the kids’ malaria episodes. So, this is exciting.

What's next?

O’MEARA: Effective malaria interventions like SMC are especially important in places like Turkana that are extremely remote, and where it’s challenging to access health care. The average distance to a healthcare facility is about 15-20 miles. It’s a huge investment for a family when their child gets sick to walk or to take a motorbike to go to a health facility. So, we feel like now that we’ve demonstrated the impact of SMC on these communities, we need to focus next on implementing this more widescale and looking at how we can deliver SMC more broadly to remote communities.

Plus, next year we're also going to try to scale this up to ten-year-olds. These older kids are not the ones who normally wind up in the hospital with life threatening malaria, but they are the ones who are transmitting to all their household members. So, by targeting those kids, then it's possible we could see a spillover or indirect effect whereby SMC protects adults through reducing transmission from the SMC treated group.

Having spent so much time on the frontlines of the malaria fight in Kenya, is malaria eradication a pipedream or a reality?

O’MEARA: For me, the question is: what's on the horizon? Answering this question would have been easier a month or so ago, but now there appear to be new challenges for malaria in East Africa. Besides immediate funding challenges, we’ve also seen the arrival of Anopheles stephensi. You have P. vivax starting to expand. Plus, there’s growing insecticide resistance. What we need are next-generation tools.

Another thing that our team does is to work on precision public health measures. Using parasite genetic techniques to identify the superspreaders or the highly connected nodes in malaria transmission networks. Our goal is to better target malaria interventions to these superspreaders which could dramatically reduce population level transmission. I think that's the direction that we must go. While malaria vaccines and SMC are vital for protecting children, they aren’t going to move the needle on transmission, which is something we must move toward doing.

What’s your hope for the future?

O’MEARA: There have been a couple things weighing heavy on my mind. The first is that in Kenya, we have two of the largest refugee camps in the world. And those refugee camps are largely stabilized by U.S. government funding. Those resources are under attack. But those refugee camps can represent a perfect sort of breeding ground for extremism and anti-American sentiment. As conditions in the camp get worse, that's a real threat. And malaria is part of the problem. It's certainly not the whole problem. Last year in Turkana, there was a massive malaria outbreak. The refugee camp called Kakuma which is home to 250,000 people was very hard hit. So, while we were doing the SMC pilot project over on one side of the county, they were having a malaria outbreak that resulted in 400,000 cases of malaria. And there's only 1.2 million people in the whole county. So that’s a huge problem. Plus, the fatality rate in the main hospital serving the refugee settlement was around 6% - which is something we haven’t seen in decades. My hope is that we can focus on getting the communities that need malaria interventions the most, the help they need.

I would also say that we shouldn't become complacent about our understanding that malaria is a global threat. We’re not immune to malaria touching down on our shores again. And I think you’ll see more and more of that - more and more tuberculosis and other health issues affecting the US in this globally connected world, if we don't pay attention to tackling these issues where they are endemic.